Healthy attachment starts neurochemically in the womb. An expectant mother, happy about her coming child, takes good care of her health and nutrition, isn’t under chronic stress and stays away from harmful toxins (like drugs and alcohol). So the baby’s brain development is optimal. When the child is born, he is immediately given to his mother, who cradles and feeds him, providing soft, nurturing sounds, sights, touch and smells.

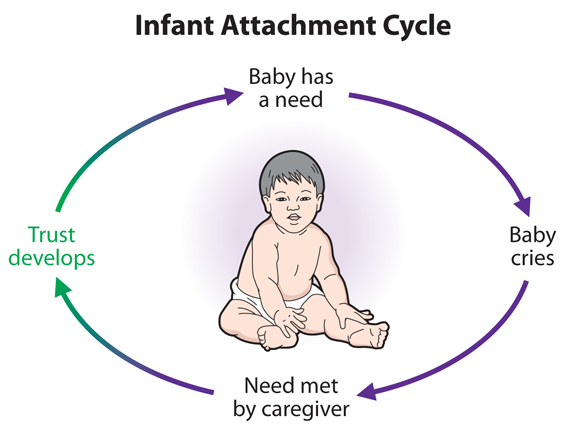

When the baby feels discomfort (hunger, tired, pain, illness), the caregivers are right there to soothe the distress. This cycle, known as the bonding (or trust) cycle, happens hundreds of times during the baby’s first year of life. Children with no impairments to their attachment will cry out when they start to dysregulate (due to some discomfort) and as they become distressed, the caregiver will meet their need in a nurturing manner, which causes the child to regulate. This cycle happens over and over throughout each day, more than 100 times in their first year of life. From this develops the child’s ability to trust and their positive world view.

There is much early childhood development research that emphasizes the importance of this cycle and of the smiles, coos, rocking and other nurturing behaviors often done by caregivers. These behaviors provide a sensory “bath” for the infant, actually stimulating brain development. Mothers will often engage in what is called “mirroring” or “matching” where they respond to the infant with the same facial expression or volume or vocal intonation. This mirroring helps connect the child to the mother, allowing the child to synchronize his breathing and regulatory systems with the mother’s. Many moms learn quickly that the way to calm a fussy baby is by remaining calm yourself, and often by adding movement and singing.

What Can Go Wrong?

There is much that can go wrong in this bonding cycle. If, for whatever reason, the child experiences discomfort and cries, but the cries are not met with a consistent nurturing response, the child does not become calmed and is not able to regulate himself. He remains in a heightened level of dysregulation. If the child cries and no caretaker comes (as in the case of neglect), then eventually the child will cease crying and cease making attempts to reach out to the world.

If the child cries and receives an inconsistent response (in the case of an abusive caregiver), the child will remain anxious, never knowing which caregiver (the loving or abusive one) will show up and whether or not his needs will be met.

If the child experiences a discomfort that is not met when the caregiver attempts to meet the need (like in the case of unmitigated medical pain or needed, but painful, medical procedures), the child will remain in a heightened state of anxiety.

All three of these scenarios, especially if they occur repeatedly, put the infant at risk for attachment impairments or attachment disorder.

Links:

- A Different Perspective

- Serve and Return – this is the terminology that Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child uses to describe this Infant Attachment Cycle